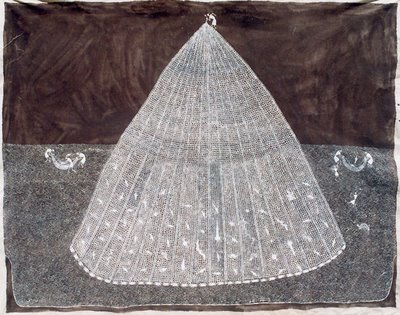

Jivya Soma Mashe, Fish men, acrylic and cowdung on canvas, 115x146 cm, 1997

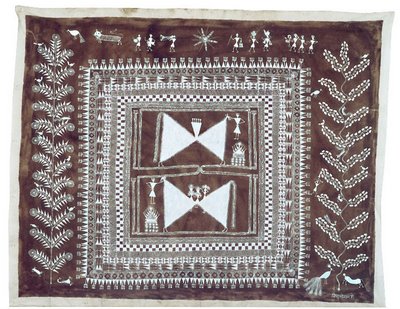

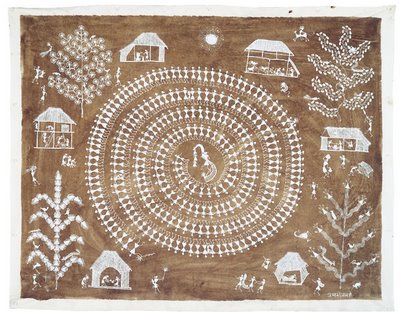

Jivya Soma Mashe, Cauk, acrylic and cowdung on canvas, 115x146 cm, 1997

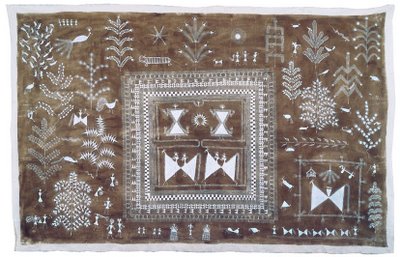

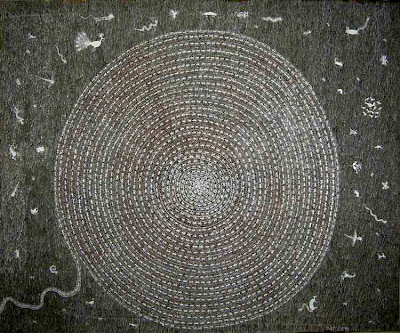

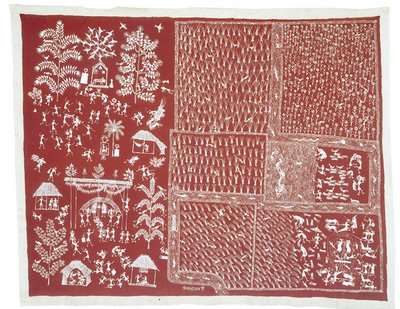

Jivya Soma Mashe, Cauk, acrylic and cowdung on canvas, 138x230 cm, 1999

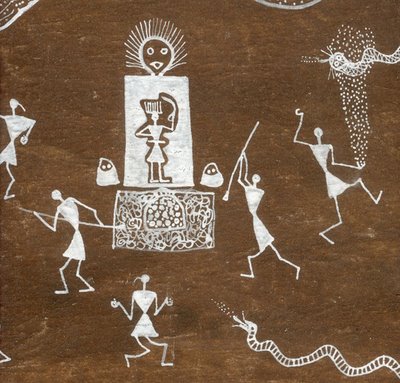

Jivya Soma Mashe, acrylic and cowdung on canvas, detail

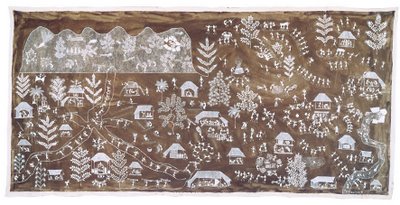

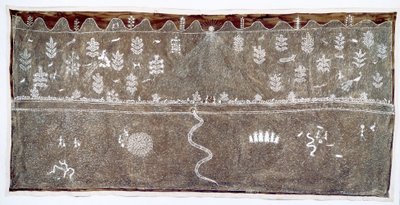

Jivya Soma Mashe, Untitled, acrylic and cowdung on canvas, 138x290 cm, 1999

Jivya Soma Mashe, Untitled, acrylic and cowdung on canvas, 138x230 cm, 1999

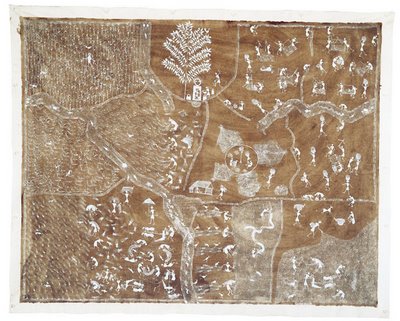

Jivya Soma Mashe, Tarpana, acrylic and cowdung on canvas, 100x126 cm, 1998

Jivya Soma Mashe, "The Ant" cowdung and acrylic on canvas, 136 x 176 cm (53,5 x 69,3 in),

Jivya Soma Mashe, acrylic and cowdung on canvas, detail

Jivya Soma Mashe and Hervé Perdriolle, Museum Kunst Palast, Germany, 2003

Jivya Soma Mashe, Untitled, acrylic and cowdung on canvas, 138x290 cm, 1999

Jivya Soma Mashe, acrylic and cowdung on canvas, detail

Jivya Soma Mashe, Untitled, acrylic and cowdung on canvas, 100x125 cm, 1998

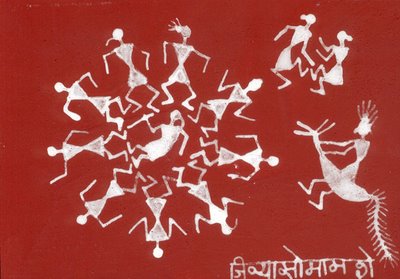

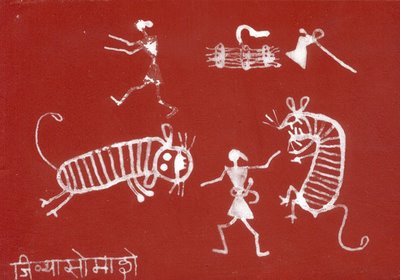

Jivya Soma Mashe, Untitled, acrylic on canvas, 115x146 cm, 1997

Jivya Soma Mashe, Untitled, acrylic on canvas, 115x146 cm, 1997

Jivya Soma Mashe, a legendary Warli artist

Indians call people hailing from tribal communities "Adivasi", which means "first inhabitants". Yet Indian tribal art is a more or less unknown quantity for us. For more than 2,000 years, the proliferation of sacred Buddhist, Jain, Hindu and Muslim arts has as good as eclipsed the tribal art of this subcontinent. One of the rare examples to have come down to us is that of the art of the Naga. The art of this tribe, erstwhile headhunters who were converted to Christianity in the 1950s, with its sculptures, ceremonial and other finery, and its architecture, rivals the most handsome pieces of the tribal art of Africa and Oceania. The handful of other known examples has reached us by way of the outstanding work carried out by ethnologists, including the studies undertaken in the 1930s by Elwin Verrier, focusing on the Gond tribe in the state of Madhya Pradesh, in the Indian heartland. Sadly, few old pieces have been preserved and chances to admire them are few and far between.

By great good fortune, however, and thanks to the Indian government and specific help from certain enlightened art lovers, the tribal art of India is not totally extinct. In the 1970s, well aware of the gradual disappearance of this artistic heritage, the Indian government came to the rescue of all its different ethnic communities. In order to be able to keep a lasting trace of the country's ritual arts--the bulk of them traditionally ephemeral--government emissaries provided these artists with other materials like paper and canvas. Being easy to transport and exhibit, these new materials have also helped to introduce these forms of ancestral art to places beyond their geographical boundaries. These paintings and drawings exhibited and sold in state-run stores also helped to augment the income of these communities, which were usually extremely impoverished. Among this art production aimed essentially at a tourist clientele, some of the more noteworthy works attracted the attention of art experts and enlightened art lovers. Back in the early 1970s, this was how most of the artists, men and women alike, who would go on to become the major representatives of Indian tribal art, were discovered. Jivya Soma Mashe was one of the first among them to gain national, and then international, recognition. Jivya Soma Mashe is a member of the Warli tribe. Located in the Thane District, about 90 miles north of Bombay, the Warli tribe still numbers some 300,000 members today. The Warli have nothing to do with Hinduism. They have their own belief system, life-style and customs.

Jivya Soma Mashe, acrylic and cowdung on canvas, detail

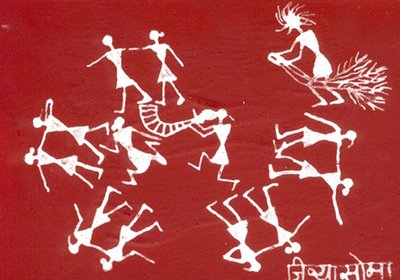

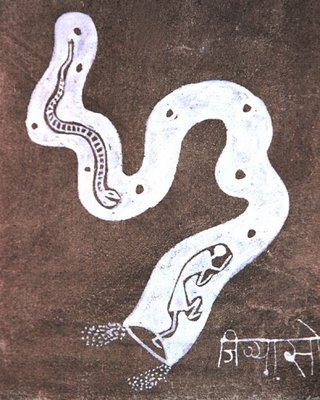

The Warli speak a dialect which has no written form. It is a mixture of words taken from Sanskrit, Maharati and Gujurati. The word Warli probably comes from the word "warla", which means a plot of land, or field. In his book "The Painted Word of the Warlis", Yashodara Damia notes that the Warlis are very probably an extension of a tradition dating back to between 2,500 and 3,000 BCE. Their wall paintings are akin to those made between 500 and 10,000 BCE in the Bhimbekta caves, in Madhya Pradesh. The extremely rudimentary visual representation in their wall paintings is constructed around a graphic vocabulary, more basic than which it is hard to get: circle, triangle and square. The circle and triangle issue from the Warli's observation of nature--the circle from their observation of the moon and the sun, and the triangle from their observation of mountains (and more specifically the sacred mountain with its sharp, pointed peak) and trees with their tops thrusting skywards. It is just the square that does not seem to come from any observation of nature; rather, it appears to be a human creation, designed to bound the sacred enclosure--the plot of land. So the central motif of each ritual painting is the square, the "cauk" or "caukat", at the centre of which we find "Palaghata", the mother goddess, symbol of fecundity and fertility. It is important to bear in mind that male deities are rare among the Warli, and that they are usually related to spirits which have assumed a human form. The central motif of these ritual paintings is surrounded mainly by scenes of hunting, fishing and farming, festivals and dances, and figures representing trees and animals. The bodies of human beings, like those of many kinds of animals, are depicted by means of two triangles, one upside down, whose respective tips touch. The upper triangle represents the torso, the lower one the pelvis. The precarious balance of these triangles symbolizes the equilibrium of the world, and the couple. This equilibrium also has the practical and larksome aspect of being easily capable of animating bodies. It is an equilibrium without which the art of Warli painters would be utterly devoid of rhythm and life.

Jivya Soma Mashe, Tarpana, rice pasta and acrylic on paper, 13x18 cm, 1997

This pictography--picture writing--is reduced to bare essentials and executed using pictorial methods which are also rudimentary. These ritual paintings are usually produced inside Warli huts, which measure about 25 x 20 feet [8 x 6 m.] and do not normally include any interior partitions. A symbolic separation divides the area between people and livestock. The walls are made of a mixture of branches, sticks, earth and cow dung, and their colour is terra cotta. It is this red ochre which is used as a background for the wall painting. The Warli use just one colour for painting--white. This white colour is obtained from a mixture of rice paste, water and gum, which acts as a bonding agent. This paint is applied with the help of a bamboo rod with the tip chewed to give it a brush-like suppleness. These wall paintings are only produced on rare occasions, like weddings and harvests. This absence of any regular artistic activity explains the extremely rough and ready style of Warli ritual paintings. Until the late 1960s, the pictorial art of this tribe was the exclusive preserve of women. During the 1970s, this ancestral ritual art would undergo a radical change. A man by the name of Jivya Soma Mashe started to paint not just on ritual occasions, but on a day-to-day basis. His talent quickly came to notice, first at a national level--it was rewarded straight from the hand of India's senior political figures, such as Nehru and Indira Gandhi, with the country's highest artistic prizes--, and in due course at an international level, when the artist started to take part in acclaimed exhibitions like "Magicians of the Earth", in 1989.

Jivya Soma Mashe, Tarpana, rice pasta and acrylic on paper, 13x18 cm, 1997

This unprecedented recognition drew a lot of young people along in Jivya Soma Mashe's wake, some of them even trained by him in workshops which were either makeshift or at times organized by government representatives. Through a daily production of paintings made to be sold, these boys swiftly acquired a know-how which was much admired by women. These days, women who still paint are few and far between, as they let men deal with this task, including when ritual paintings are called for. Many of these young painters were, and still are, invited to exhibit their work abroad, as part of both institutional and private programmes. Among them, Shantaram Tumbada has seen one of his works featured on the wall of an apartment block at Villeurbanne, near Lyons (France); his style shows a rare graphic maturity and lends his simplest drawings the visual effectiveness of the very best of pictograms.

The story of Jivya Soma Mashe is unusual, not to say one-off. He was abandoned by his family as a very young boy, and withdrew into total silence. In those days, the only way he expressed himself was to make drawings on the ground. This strange pastime quickly earned him a special status within his community. The first government emissaries who were responsible for preserving and promoting the art of the Warli were immediately amazed by the artistic skills of this young man. From that period of withdrawal and introversion, Jivya Soma Mashe appears to have retained an extraordinary imaginary capacity, but above all a most exceptional sensibility. The fact of working on surfaces like paper and canvas has helped him to break loose from the restrictions of the uneven and jagged surface of the wall. Jivya Soma Mashe has turned the abrupt look of ephemeral paintings into a free and candid style which gives off its very own sensibility.

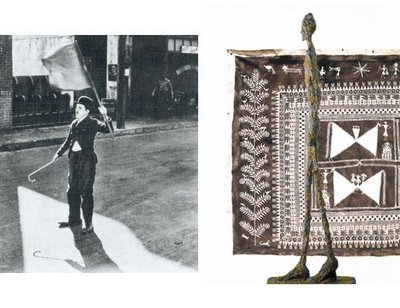

Walking is an ever-present feature both in Warli landscapes, with its countless tracks and trails criss-crossing the ground like the traces of some unfinished process of sedentarization, and in the paintings of Jivya Soma Mashe. In his paintings, walking is also included in the form of tracks, usually represented by a lone line. One or more lines, running across and structuring the canvas, invite us to follow his ever-moving figures, his "walkers" whose bold, rudimentary forms conjure up the likewise rudimentary and resolute silhouettes of other famous "walkers" represented, or depicted, by Alberto Giacometti, Charlie Chaplin, and Jacques Tati.

Charlie Chaplin, Aberto Giacometti et Jivya Soma Mashe

Jivya Soma Mashe, Tarpana, rice pasta and acrylic on paper, 13x18 cm, 1997

Richard Long, work in progress near of the Jivya Soma Mashe house, India 2003

When you take a close look at Jivya Soma Mashe's paintings, what is most striking about them is the "movement", the quality of the detail, the lightness and, at the same time, the precision of line and stroke. There is no such thing as hesitancy in Jivya Soma Mashe's work. The artist goes straight for the crux in his drawing and his composition alike. Directly, without beating about the bush, and with all the simplicity of what is obvious, ingenuous and natural. This comes across in every detail of his work. Strokes, lines and dots abound, teeming on the canvas, vibrating and harmoniously interweaving in deft compositions, which themselves reinforce the vibration of the whole. The detail and the overall composition of the work both help its movement. The recurrent themes of his work--the everyday activities of his family and friends and Warli legends--are also the pretext for a constant eulogy of movement. "There are human beings, birds, animals, insects, etc. Day and night there is movement. Life is movement." Through his subjects, Jivya Soma Mashe describes the deep-seated feeling which drives the Warli soul. As Adivasi--first inhabitants--the Warli talk to us of the most ancient of times and conjure up an ancestral culture, an in-depth study of which would possibly help to reveal some of the cultural and religious foundations of modern India.

Hervé Perdriolle

Jivya Soma Mashe, acrylic and cowdung on canvas, detail

First ritual steps (Hindu), on a 'nan' or Indian bread's path, of the niece of Viswas Kulkarni (left on the group photo). Viswas has learnt the dialect of the Warli tribe from his uncle, Baskar Kulkarni, the first emissary of the Indian government to be interested in the art of this tribe. It is with Viswas Kulkarni that I have done, in 1996, my first steps in the Warli land.

Texte, photos and collection : Herve Perdriolle

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

"There are people, birds, animals, insect etc. Movement continues throughout the day and night. Life is movement" Jivya Soma Mashe

Hervé Perdriolle invite you in his new art gallery in apartment in the heart of the Latin Quarter, rue Gay Lussac, Paris, to discover his collection of tribal & folk Indian contemporary arts.

> VISIT BY APOINTMENT ONLYHervé Perdriolle vous invite à découvrir sa collection d'art contemporain rural de l'Inde dans son appartement galerie, rue Gay Lussac à Paris.

> VISITE SUR RENDEZ-VOUS> INFORMATION AND CONTACT

> VISIT BY APOINTMENT ONLYHervé Perdriolle vous invite à découvrir sa collection d'art contemporain rural de l'Inde dans son appartement galerie, rue Gay Lussac à Paris.

> VISITE SUR RENDEZ-VOUS> INFORMATION AND CONTACT